So I was in Seoul recently and finally visited the DMZ, which I’ve wanted to do for years but never found the chance to. It started out mainly as idle interest in seeing history’s physical manifestation, but over the years, my desire to see the place became inseparable from my growing interest in the relationship between tourism and remembrance, especially with regards to landscapes of trauma. This duality of public and private is something that I’ve been preoccupied with for many years, in academia this manifests amongst other things in my study of traumatic landscapes (via geographical disasters, physical warfare, medical warfare, and how this affects the people linked to these places), in real life, it is the source of my perpetual wrestle with the commercialisation of the public self. You know how it is.

As someone who travels a lot, I believe strongly in the importance of tourism, but I’ve also seen my fair share of very badly behaved tourists. When you’re being rudely shoved at Disneyland you can, on some level, roll your eyes and shrug it off, but there are cases that sit in a far greyer zone – when tourists obliviously disrespect the cultural customs of a place, when they cause disturbances through ignorance, when they feel entitled to certain modes of behaviour because they’d put their dollar down to access a destination. Things like this give rise to the widely concurred cliche that tourism is often a negative force. But the alternative option isn’t feasible either – no country is going to close up against tourism, not in the age of wanderlust and slashed airfares, not in the age where it’s such a major economic driving force, and so most people just accept it as something that’s a necessary irritant with a sort of grumpy tolerance.

I do think, however, that there is a case to be made for the necessity of tourism in relation to landscapes of war and trauma, and it’s something that my recent trip to the DMZ confirmed.

We can see the coexisting relationship between tourism and landscapes of trauma globally (auschwitz) and closer to home (fort canning/siloso), but the DMZ is unique in the sense that the two sides are still at war. The DMZ currently wraps around one of the most dangerous borders in the world, and that alone draws curious tourists to it by the droves. It’s mad hard to get tickets to visit the DMZ, you have to book way in advance. I got my tickets on Klook, but due to fluctuations and security concerns from the UN, the operator checked back with us several times to update us on the situation and confirm that we were still interested in taking the tour given the UN’s stance. Any illusions I had about the DMZ’s political issues being simply a chapter in a history textbook dissolved then, and yet, this didnt deter tourists in the least: when we finally got on the bus to go to the DMZ, it was full.

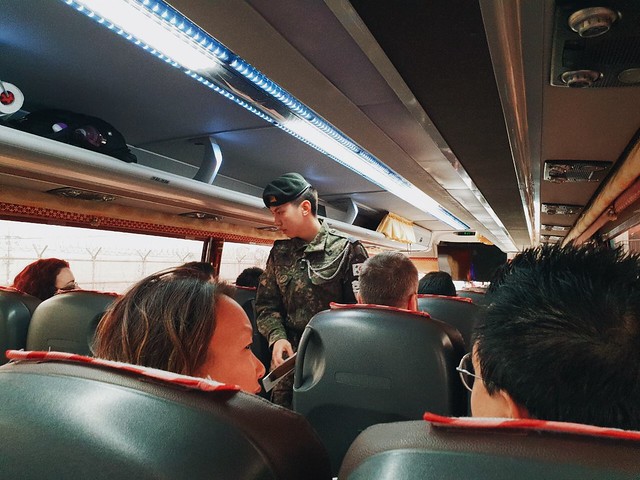

Visiting the DMZ is so strict that you’re not allowed to drive in by yourself or anything like that. It’s the safest and currently the only option to go with a tour bus because the DMZ has now restricted civilian access and requires mandatory military clearance and escort. But with a tour, everything is arranged for you, and you can actually ask the guide when you dont understand something (I was constantly running after my guide to ask her stuff, I think she was starting to feel guilty for neglecting the others). The DMZ isn’t like a regular tourist destination where you can just wander off by yourself, you’re not allowed to, first and foremost, and don’t think you can sneak off and go look for the actual border because it’s prohibited for a reason – it’s one of the most dangerous borders in the world and the most heavily militarised, so there actually have been several terrible instances with civilians and soldiers on both sides of the border, and I’m surprised (and thankful) that we’re allowed to visit at all.

Most photos in this post are taken on my phone, it felt too conspicuous to be using my DSLR

The soldier got off, we trundled on.

Once we got into the heart of the DMZ, we started the tour off by being hustled into a dark theatre where we were shown a film on the history between the North and South. It consisted of a very intense five minutes of telling us that North Korea ruined life for Koreans as they knew it with their penchant for warfare and bombs, and ended off by totally changing track, informing us that the DMZ was a haven of peace and nature, where flora flourished and animals roamed freely. This is true – I did some research later and found out that the DMZ is a kind of accidental nature park – it’s so dangerous for humans that no one can live there, so nature has taken over and it’s now one of the most world’s most well-preserved areas of temperate habitat. They wanted to turn it into a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve because so many endangered plant and animal species live there, but this was eventually blocked by North Korea because it violated their Armistice agreement. A pity. But none of this was apparent when we were actually in the DMZ – partially because of the Spring-Summer transition and partially because of the mood, the entire place looked moody and deserted, and nothing like the land of life and freedom that the film purported.

The actual DMZ, as seen via the bus windows

This sense of hopelessness persisted throughout the rest of the tour, nestling in the disconnect between the determined cheerfulness and optimism of the DMZ’s narrative and the reality of the situation. We visited the Third Tunnel of Aggression, a tunnel extending from North Korea under the DMZ which, when discovered, was passed off as a coal mine tunnel rather than an infiltration tunnel. We were shown the dynamite holes and ushered down the tunnel, where we walked in a straight and claustrophobic line to see the third barricade between the tunnel and the actual Military Demarcation Line. I thought to myself, if this tunnel collapses now I will literally die. I felt a heat rise up from within me and I batted it away. The tour guide said, We’ve only discovered four tunnels so far. Who knows how many more there are! and I felt her despair infect me.

Later a friend related what his South Korean friend described to him as the essence of his lived experience: sea legs, always feeling like his internal balance was off, trying perpetually to regain balance while knowing that at any time the ground below them could explode upwards and they’d be back in the heart of the war. Desperate anger, in other words. And espousing an intimate fear so different from the technicolored face korea typically showed to the world.

After lunch we wandered back to the bus and waited for the JSA portion of the tour to start, all hyped up by the Canadian dad. We got on the bus and it started moving. Less than five meters later it stopped and someone got on the bus, muttering to the tour guide. We were all staring at her at this point, kind of because there was nowhere else to look. And then she said into a mic:

Very bad news sorry. The UN has closed the JSA indefinitely. You need to go back to South Korea now. Very sorry.

Someone else on the bus started protesting, asking if they could reschedule. She shook her head.

We dont know if it’s going to open again. You’re going back to South Korea now sorry. You can get a refund for the JSA portion later.

We had no choice in the matter, back we went. And so the physical experience of our tour concluded.

But the lingering effects of the tour moved forward with us. Later on, while walking back to our hotel, Martin and I mused over the strange sense of insecurity we harboured throughout the tour. It was clear that despite being marketed as a tourist attraction, we were expected to be more like observers than active participants in the tourist activity, and the sense of tense anticipation that had cumulated in being blindsided by a UN order to close the JSA only released us when we’d been deposited back in the city center. I couldn’t imagine living under the thumb of such situational uncertainty, I realised then that despite my previous belief that everyone more or less feels uncertainty regarding their future, there was an invisible privilege in feeling that uncertainty only because of an individual conundrum re: one’s career/life path/ choices. When it was a situational uncertainty that pervaded the entire nation, the uncertainty became a low level humming that you carried everywhere with you, that you didn’t want but had no way to be rid of. I suddenly remembered the glances my korean friends had exchanged when I had cheerfully told them several days prior at dinner that I’d be visiting the DMZ, and I felt embarrassed.

It seems timely that I am now in April 2018 recounting my experiences there – just a couple of weeks ago, rumours surfaced that the North and South Korea might finally be putting an end to their 65 year war. The South Korea speakers that blast propaganda nonstop across the borders have just been silenced for the first time in 2 years. And with the Trump-Kim talks on the table, every major news outlet is convinced that the demilitarisation is either on its way or going to stay exactly as status quo. A time of flux, in other words, with the future’s uncertainty taking on a more optimistic tone than it has in ages. But even so, what comes ahead does not negate what came before. And so remembrance is more important than ever.

Which brings me back to my initial point – that tourism has its unique place in the ecosystem of remembrance, especially in relation to landscapes of trauma and war. Tourism is certainly not the only thing mediating memories of war, there is already an existing framework in place that plays out in many ways throughout pop culture – we have movies (pearl harbour, die leben der anderen), books (pachinko, a dictionary of mutual understanding, the book thief), songs (dixie chicks’ travelin soldier), poetry (Julia Vinograd’s GINSBERG), and so on. All of it comes together to form a web of myth that mimics the tradition of verbal storytelling, and the cumulative effect creates an empathetic acknowledgement of traumatic historical events.

And this is also where tourism fits in. When done properly, the tourist experience creates a cognitive phenomenon by manufacturing an emotional and spatial proximity to war (Geoffrey Bird, University of Brighton). It acknowledges, on an individual level, the traumatic experiences lived by people past. And it goes on to become part of the continual negotiation between the country’s representation of their memories of war and an international recognition of the nation’s culture.

Additionally, the act of tourism and remembrance is especially important with regards to the DMZ in light of recent developments and movements towards peace. When I began this post I spoke about landscapes of trauma generally, but intrinsic to the very definition of trauma is the fact that all discussion of trauma is past. In the same way that the term “survivor” is only used in context of an incident that is now over, trauma at an individual level is also only discussed after the event because the traumatic incident is incomprehensible when happening. The DMZ differs from the traditional landscapes of trauma because the act of visiting it is the tourism of a landscape of trauma that hasnt been fully created yet and therefore is still being lived and experienced. As compared to auschwitz, which has passed and therefore is indelible, the DMZ represents the present struggle between two sides of Korea, the effects of which leak into the everyday lives of koreans. We have not yet reached a point where the dialogue around the DMZ has been romanticised and coloured by the lens of nostalgia as so many historical sites often are, but we soon may, which is why now is precisely the time to see it, talk about it, and remember it for what it is. Which is, essentially, to become the witness – part of the process of the creation of history.

One last note on tourism. The active engagement with a place’s history as it is being created and lived allows you, the tourist, to fully appreciate the delicacy of the situation in present tense. But with that comes a responsibility to engage thoughtfully and respectfully, which entails a code of conduct whilst there (basic sensitivity, an awareness of language used, and respectful dressing). There is much of tourism and travel that can be taken at face value: the visual splendour of foreign scenery, the childlike excitement at seeing first snow, the first bite of an incredible meal.. but we would do well to remember that there are also some forms of tourism that can literally take us further, that can broaden our perspectives, our capacity for empathy, and help us appreciate our humanity on a deeper level. Herein we find the mythical quality of travel that modern wanderlust culture frequently touts, the type of tourism that catalyses personal development and eye opening experiences. The DMZ tour is one of them. And that alone renders the trip totally worth it.

This post was written in collaboration with Klook Singapore

You can book your tour to the DMZ on Klook here

There is also a $10 off Korea activities promo on Klook, running till the end of May

T&Cs apply, obviously

x

Jem